Note: This is the final article in a three-part series on valuation thoughts for common sectors of venture-capital investment. The first article, which attempts to make sense of the SaaS revenue multiple, can be found here; the second, on public marketplaces can be found here.

Over the past year, the VC-backed hardware category got a big boost — Roku was the best-performing tech IPO of 2017 and Ring was acquired by Amazon for a price rumored to exceed $1 billion. In addition to selling into large, strategic markets, both companies have excellent business models. Ring sells a high-margin subscription across a high percentage of its customer base and Roku successfully monetizes its 19 million users through ads and licensing fees.

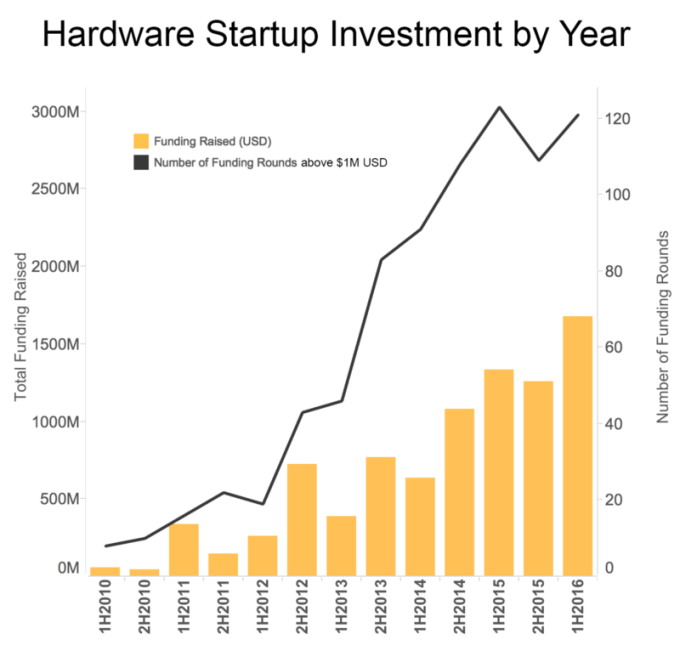

In the context of these splashy exits, it is interesting to consider the key factors that have made for valuable hardware companies against a backdrop of an investment sector that has often been maligned through the years, as I’m sure we’ve all heard the trope that “hardware is hard.” Despite this perception, hardware investment has grown much faster than the overall VC market since 2010, as shown below.

Source: TechCrunch

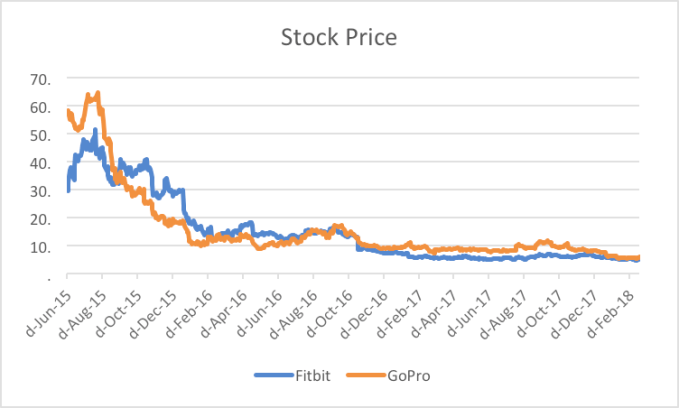

A large part of this investment growth has to do with the fact that we’ve seen larger exits in hardware over the past few years than ever before. Starting with Dropcam’s* $555 million acquisition in 2014, we’ve seen a number of impressive outcomes in the category, from large acquisitions like Oculus ($2 billion), Beats ($3 billion) and Nest ($3.2 billion) to IPOs like GoPro ($1.2 billion), Fitbit ($3 billion) and Roku* ($1.3 billion)**. Unfortunately for the sector, a few of these companies have underperformed since exit; notably, GoPro and Fitbit have both cratered in the public markets.

As of April 3, 2018, both stocks traded at less than 1x trailing revenue, a far cry from the multiples of forward revenue given to other tech companies. Roku, on the other hand, continues to perform as a stock market darling, trading at approximately 6x trailing revenue and a market cap of $3.1 billion. What sets them so far apart?

The simple answer is their business model — Roku generates a significant amount of high gross margin platform revenue, while GoPro and Fitbit are reliant on continued hardware sales to drive future business, a revenue stream that has been stagnant to declining. However, Roku’s platform is one successful hardware business model; in this article I’ll explore four others — Attach, Replacement, Razor and Blades and Chunk.

Attach

“Attaching” a high gross margin annuity stream from a subscription to a hardware sale is a goal for many hardware startups. However, this is often easier said than done — as it’s critical to nail the alignment of the subscription service to the core value proposition of the hardware.

For example, Fitbit rolled out coaching, but people buy Fitbit to track activity and sleep — and this mismatch resulted in a low attach rate. On the other hand, Ring’s subscription allows users to view past doorbell activity, which aligns perfectly with customers looking to improve home security. Similarly, Dropcam sold a subscription for video storage, and at an approximate 40 percent attach rate created a strong economic model. Generally, we’ve found that the attach rate necessary to create a viable business should be at least in the 15-20 percent range.

Platform

Unlike the “Attach” business model that sells services directly related to improving the core functionality of the hardware device, “Platform” business models create ancillary revenue streams that materialize when users regularly engage with their hardware. I consider Roku or Apple to be in this category; by having us glued to our smartphones or TV screens, these companies earn the privilege of monetizing an app store or serving us targeted advertisements. Here, the revenue stream is not tied directly to the initial sale, and can conceivably scale well beyond the hardware margin that is generated.

In fact, AWS is one of the more successful recent examples of a hardware platform — by originally farming out the capacity from existing servers in use by the company, Amazon has generated an enormously profitable business, with more than $5 billion in quarterly revenue.

Replacement

Despite the amazing economics of Apple’s App Store, as of the company’s latest quarterly earnings report, less than 10 percent of their nearly $80 billion in quarterly revenue came from the “Services” category, which includes their digital content and services such as the App Store.

What really drives value to Apple is the replacement rate of their core money-maker — the iPhone. With the average consumer upgrading their iPhone every two to three years, Apple creates a massive recurring revenue stream that continues to compound with growth in the install base. Contrast this with GoPro, where part of the reason for its poor market performance has been its inability to get customers to buy a new camera — once you have a camera that works “well enough” there is little incentive to come back for more.

Razor and Blades

The best example of this is Dollar Shave Club, which quite literally sold razors and blades on its way to a $1 billion acquisition by Unilever. This business model usually involves a low or zero gross margin sale on the initial “Razor” followed by a long-term recurring subscription of “Blades,” without which the original hardware product wouldn’t work. Recent venture examples include categories like 3D printers, but this model isn’t anything new — think of your coffee machine!

Chunk

Is it still possible to build a large hardware business if you don’t have any of the recurring revenue models mentioned above? Yes — just try to make thousands of dollars in gross profit every time you sell something — like Tesla does. At 23 percent gross margin and an average selling price in the $100,000 range, you’d need more than a lifetime of iPhones to even approach one car’s worth of margin!

So, while I don’t think anyone would disagree that building a successful hardware business has quite literally many more moving parts than software, it’s interesting to consider the nuances of different hardware business models.

While it’s clear that in most cases, recurring revenue is king, it’s difficult to say that any of these models are intrinsically more superior, as large businesses have been built in each of the five categories covered above. However, if forced to choose, a “Platform” model seems to offer the most unbounded upside as it’s indicative of a higher engagement product and isn’t indexed to the original value of the product (some people certainly spend more on the App Store than on the iPhone purchase).

While it’s easy to take a narrow view of VC-hardware investing based on the outcome of a few splashy tech gadgets, broadening our aperture just a bit shows us that large hardware businesses have been built across a variety of industries and business models, and many more successes are yet to come.

*Indicates a Menlo Ventures investment

**Initial value at IPO